FOREVER STRONG – Some comments on the book by J C Wall.

It’s clear from these notes that Jack had a few strong opinions about a number of things in this book. I think most interestingly, there is a tangible anger regarding the description by Alex Simpson of his discussion with Jack Bailey regarding who would fly the 100th Op in JN-Mike.

All extracts and photograph of NE181 ‘The Captains Fancy’ from ‘Forever Strong – The Story of 75 Squadron RNZAF 1916-1990’, by Norman Franks. Published by Random Century New Zealand Ltd. 1991.

Page 72. Chapter 9 – Newmarket. November 1942 – February 1943.

Five aircraft went to Turin the next night, bombing markers laid down by Pathfinder aircraft, but only three got through. One returned with turret and intercom problems, while the other failed to gain enough height to clear the Alps and returned.

‘The Operation to Turin on 20.11.42 was the first use of Stirlings by 75 Squadron and only 4 Aircraft were detailed. This was my first Operation and only 2 of us reached the target and the other 2 returned early’.

Page 74. Chapter 9 – Newmarket. November 1942 – February 1943.

As January began, it was back to ’Gardening’ — a good stand-by when full Ops were not possible. Indeed, except for a couple of raids upon Lorient, the trips that month were all mine-laying. The Lorient trip on 23 January took Sergeant R.M. Kidd and his crew from the squadron — the first loss of 1943. Kidd in fact managed to evade, but the rest of his crew died.

Even on ’Gardening’ trips, enemy reception could be rough. Over the Gironde Estuary on 18 January, Sergeant Bennett, on his first trip, met with a hot reception. But successful evasive action after combats with three enemy aircraft enabled Bennett to bring his crew home safely.

‘Mine laying (Gardening) was usually an easy trip but we had some shockers. Our 4th. Operation was one when we nearly ended our lives and is mentioned in the Citation for my D.F.C.’

Page 78. Chapter 10 – The Battle of the Ruhr. March – May 1943.

Then it was Berlin again, and yet again, on 27 and 29 March. Sergeant Bartlett made both trips:

on the first raid it took us 7 hours 40 minutes — quite a quiet trip; straight in, no trouble with the bomb run, bombs gone, and straight out, left hard circuit and away home. Nothing wrong with their defences, they were all there. I don’t know what made us so immune, which is more than can be said for the 29th! It took us 81/2 hours to get home -— on three engines. After the Lord Mayor’s Show, we floated up to the target. Then the rear gunner screamed: ’Fighter on the port quarter!’ An attack started and I looked down the rear of the aircraft and saw a line of incendiary shells going through the fuselage. Then the mid-upper cried that it was coming in again from the port for a second attack. We heard both gunners cry out they’d got it — both claimed it. Then a searchlight caught us, passing us from cone to cone, trying to get us out of the target area, to blow us to pieces. Then the port outer engine caught fire with a long trail of flame from it. l told the skipper to try a steep dive and he went down from 14,000 to about 9 to 10,000 feet, and we got away with it and got home despite another two fighter attacks — nobody hurt — our mid-upper claiming a second kill.

I recall our WOP, Rupert Moss, seeing a couple of swans over Berlin at about 14,000 feet and reported it to the Intelligence Officer when we got back — which he duly noted!

‘We went to Berlin on 1st March, on 27th March and then on the 29th.March 1943‘.

Page 83. Chapter 10 – The Battle of the Ruhr. March – May 1943.

At the end of the month, came a return to mining, first to the Frisian Islands, then to Kiel Bay and yet another disaster. Eight crews were assigned to go to Kiel on the night of 28/29 April, part of a mammoth force of 207 aircraft to mine the seas off Heligoland, in the River Elbe, and in the Great and Little Belts. An estimated 593 mines were sent into the water but the aircraft met much flak both from the shore and flak-ships strategically located by the Germans. Although it was a huge operation, the losses were unexpectedly high, no fewer than 22 aircraft — 7 Lancasters, 7 Stirlings, 6 Wellingtons and two Halifaxes —- failing to return. Four of the Stirlings were from 75 Squadron -— 28 men killed!

‘Another disaster when Gardening in Kiel Bay. 8 of us from the Squadron were detailed and one returned early. Out of the other 7 Aircraft only 3 of us completed and the other 4 failed to return – the 28 crew members were all killed’.

Page 84. Chapter 10 – The Battle of the Ruhr. March – May 1943.

Wing Commander Wyatt remembers:

I took over 75 Squadron on 3rd May 1943. I’d been flying with 15 Squadron, originally from Boume, a satellite of Oakington. I’d been missing from a raid on Turin and had crash landed in Spain, but eventually re-joined the squadron just as it was about to move to Mildenhall. I hadn’t been there many weeks when I was sent for by Group HQ and was told about the state of 75 Squadron and was asked if I’d like the job as CO, but was told it was going to be a very tough one.

The morale of 75 at the time was very low. Their operational success rate was absolutely appalling and was one of the worst in Bomber Command. There were various reasons for it though.

The airfield at Newmarket was so close to the town — the Messes were virtually in the town — and there was far too much hospitality. All these New Zealanders rather fascinated the horse racing fraternity and Newmarket was the only place where horse racing continued during the war. They would not, of course, allow the racecourse to be turned into a proper airfield, with proper runways and so on. We used the Jockey Club which is where I had my sleeping quarters and the Officer’s Mess was just on the corner of the road south of the Club, on the main street.

The chaps were being entertained far too much and I think there was a terrible number of sore heads on a lot of mornings. It seemed to me they were enjoying life rather more in Newmarket and had begun to lose sight of the main reason for being there. The AOC outlined all this to me and said it was up to me to sort them out and get them back to being an operational squadron.

‘Wing Commander Wyatt spoke at one of our reunions and more or less repeated the comments in the book. In my view which was shared by many others it was absolute rubbish. We were not “living it up” at Newmarket and the main reason for the move to Mepal was because Newmarket only had grass runways’.

Page 99. Chapter 12 – Mepal. June – September 1943.

Norman Bartlett recalled the time a Lancaster was found right above them over the target:

We were on the bombing run and I was watching for other aircraft when we heard a cry. Looking round, Jack Brewster, our navigator, was pointing upwards, open mouthed, his face all twisted with fright. I looked up and directly above, about 200 feet, was a Lancaster, with bomb doors open, ready to drop a 4000 pound ‘cookie’. It was too late to do anything before the cookie dropped and as it passed us, it turned over and went by in a vertical position rather than horizontal, which probably saved us. Jack heaved a huge sigh of relief — and so did I!

‘Norman Bartlett was our Flight Engineer and Jack Brewster our Navigator at Mepal on Lancasters. As Norman’s comments follows the mention of ‘Stirlings flying under

Lancasters’, readers could be misled into thinking we were in a Stirling when we were nearly hit by a 4,000lb. Cookie. We were in a Lancaster and the other one was either at the wrong height or bombing at the wrong time. I did not see the Cookie as I was in the front of the Aircraft on my stomach looking through my Bomb Sight giving the Pilot instructions ready to bomb’.

Page 151. Chapter 18 – The Last Winter. December 1944 – February 1945.

‘Under the photo of “The Captains Fancy” it states that Alex Simpson flew it on its 101st on the 5th January but it did not complete its 100th until the 29th Jan and also Alex did not take it on its 101st – we did on 2nd Feb’.

Page 152. Chapter 18 – The Last Winter. December 1944 – February 1945.

Alex Simpson recalls an important event at this time:

Squadron Leader Jack Bailey, ‘C’ Flight Commander, usually flew Lanc NE181 ‘M’ for Mike— named ‘The Captain’s Fancy’, which was a dog of an aircraft and I guess understandably so, as it was approaching its 100th operation. When the time came, Jack asked me if I would take ‘Mike’ to Ludwigshaven on the 5th —- the day after my 21st birthday. I protested for I had a very good aircraft of my own, and I had flown ‘Mike’ previously — in December.

It became apparent that Jack was superstitious about flying ‘Mike’ on its 100th, so in the end I agreed. After the operation, we did an in-depth study of the aircraft’s log book and associated paper work and found to ]ack’s geat surprise that he had already done the 100th — I had in fact done the 101st!

Jack and I tried very hard through Bill Jordan, the NZ High Commissioner in the UK, to get permission to fly ]N—M out of New Zealand on a flag-waving War Bonds tour, as it was then the first NZ aircraft to reach 100 operations, but we never got approval. I delivered ‘Mike’ to Waterbeach on 17th February, and it was later struck off charge on 30th September 1947.

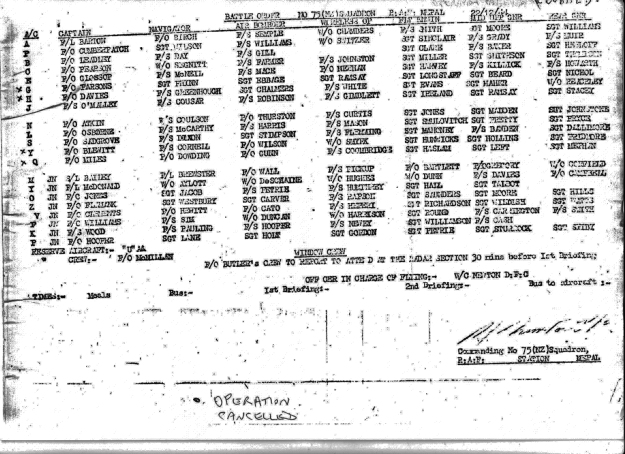

‘The comments made by Alex Simpson regarding Jack Bailey are not a true record of events. I am very annoyed that he implies that Jack was frightened to take the aircraft on its 100th. We were all looking forward to being the crew that did the 100th in an aircraft that we had flown most of our Operations in. Jack was one of the most fearless, dedicated Pilots with the Squagron and as he had died some years before the book was compiled he could not put the record right. I had no knowledge of the contents of the book until I received the final copy after printing. We flew in “The Captains Fancy” to Krefeld for its 100th on the 29th Jan and this is confirmed in the book ‘Lancaster at War – 2′ also in Jack Bailey’s Citation for the Bar to his D.F.C. dated 16.4.45, also in my log book. Fred Woolterton – one of our ground staff – in the photo has also recently confirmed this. We flew it to Wiesbaden on 2nd. Feb for its 101st. and to Wessel on the 16th.Feb for its 102nd. I have an actual Bombing Photo of this last Operation showing Target, Date, Pilot and the Aircraft letter. Apart from Alex’s dates; all being wrong, Jack, as Flight Commander, would not have asked if he would take it but would have simply detailed him………’.

Page 155. Chapter 19 – Victory in Europe. February – May 1945.

A daylight raid on Osterfeld by 21 of the squadron’s aircraft took place on 22 February, flak trying desperately to inflict hurt and injury. Flight Sergeant T. Cox had his starboard inner hit by flak, but the flames were put out by cutting the petrol and using the extinguisher. Flying Officer H. Russell’s bomber was also hit, the prop on the port inner and damage to the leading edge of the wing between his two starboard engines giving some moments of concern. Flight Lieutenant Doug Sadgrove had his port outer hit on the bomb run but he continued on, while Warrant Officer E. Ohlson also had an engine knocked out. Flight Lieutenant K. Jones lost an engine on the way out and had to abort.

‘I am surprised that no mention of Jack Bailey or his crew was made for this raid to Osterfeld as we led the Squadron and Jack was awarded the Bar to his D.F.C. for his courage and leadership on this Operation. We were hit in ail engines and had to feather one over the target and ended with 37 holes – no injuries. Despite this I had a very good Bombing Photo at 19.000ft.’.